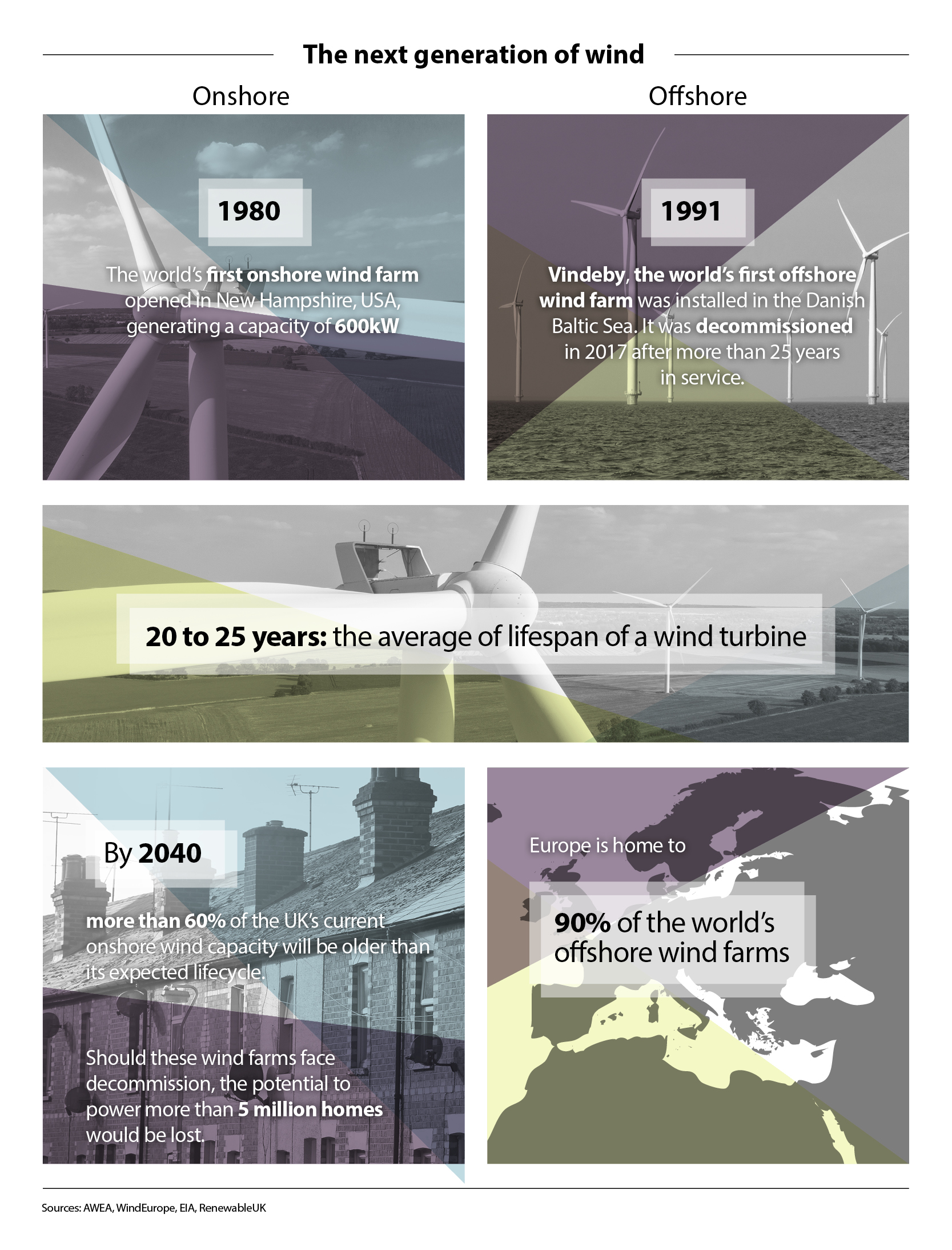

The first wind farm in the UK opened in Cornwall in 1991, and with wind turbines having an average lifespan of 20 to 25 years, the first generation of projects have started coming to the end of their lives.

That raises the question of what to do with the sites. They can be decommissioned and returned to their natural state, but there is another option – to ‘repower’ them by removing the old turbines and replacing them with newer equipment.

“From a societal and economic point of view, it makes a lot of sense to repower – it’s a quick, easy and cheap way to take advantage of the sites with the best wind and reduce carbon,” says Ben Backwell, CEO of the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). “Because the technology has improved so much, you can make incredible gains – you can replace eight old turbines with one new one and still produce more power.”

The chief driver for repowering is the vast improvement in turbine technology over the last 10 years, according to UK wind turbine installer, 3R Energy. Modern units “are quieter, more reliable and capable of producing more electricity, more efficiently,” it says.

This improvement comes in part simply because new turbines are bigger and thus able to capture more of the wind’s energy, as well as having access to stronger, more consistent winds higher off the ground. But it’s also because the technology and its role in the wider power system is now much better understood.

“Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, wind was a novel way of generating electricity and the industry had to be supported to reach the levels of penetration we have today,” says Lindsay McQuade, CEO of ScottishPower Renewables. “With that there was uncertainty and risk. There has been a huge amount of innovation over the last 25 years. We have seen a move from 200kW turbines about 20-30 ft high to turbines up to 10 times that height that are capable of generating up to 4MW.”

“Repowering creates a new wind farm where there was an old one,” McQuade says. “But we also understand much more about what the asset does, how it works with the grid and how we can control the power.”

There are many advantages to repowering on existing sites, including the fact that there is existing infrastructure, good knowledge of the wind resource and a record of the conditions on site. In addition, “the local community often feel an affinity with the technology as they have lived with it for a number of years,” McQuade says.

But while repowering should be easier than developing a completely new site, it is not necessarily straightforward. While much existing infrastructure is already there, the turbines are so much bigger that facilities such as bases, grid connections and cabling often have to be upgraded. Even access roads may need to be upgraded because the new turbines are so much heavier than the machines they are replacing. At ScottishPower’s Coal Clough development in north west England, the company replaced 24 400kW turbines with eight 2MW devices. “Because of the change in scale, it was effectively a new planning application,” McQuade says.

Yet there are many factors in favour of repowering – the cost of wind power has come down sharply, financiers are much more comfortable with both the technology and the financing structure of deals, and there is a range of complementary innovations that can make projects even more economically compelling.

Battery storage is rapidly falling in price and enabling wind projects to store power they generate at off peak times and sell it when demand, and prices are higher. Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence help to integrate wind power into the grid more effectively.

Another opportunity is hybridisation, says GWEC’s Backwell. “Bahia, in north east Brazil, for example, has the best wind resources in the world, but it tends to blow at night. That means there is a lot of spare transmission capacity during the day – and it’s very sunny, so it makes sense to put a lot of solar panels around the wind farms and use that capacity.”

While repowering is most prevalent in onshore wind because of the maturity of the industry, other renewable sectors are also likely to repower. “There’s no reason the same can’t happen with offshore wind,” Backwell says. “The technology has moved on very quickly, there are lots of very good sites and infrastructure you can use – although decommissioning costs will be higher.”

By 2022, 22 GW of Europe’s installed wind capacity will be more than 20 years old according to WindEurope’s Wind Energy Outlook. The powering up of the next generation of wind turbines marks a new chapter in the wind industry’s history.