For decades, the only commercially viable way to store energy at any scale was pumped hydro-electric, whereby water is pumped from a lower reservoir off peak and released to drive turbines when demand is high.

However, pumped hydro is a technology that has specific requirements, namely a valley suitable for a dam and an upper and lower reservoir.

Another option was needed, one that is less geographically constrained. But as recently as 2016, a report from McKinsey & Co. observed that many companies believe ‘that [battery] storage will not be economical any time soon. That pessimism cannot be dismissed. The transformative future of energy storage has been just around the corner for some time, and at the moment, storage constitutes a very small drop in a very large ocean.’

But in that same year, battery storage projects were installed in Australia and the United States in response to two different disasters – the overloading of the grid due to some of the most severe storms in half a century in South Australia, and the huge leak at the Aliso Canyon gas storage facility in California. Both projects were deployed within months and quickly proved their reliability and versatility. Battery storage had proved itself. At the same time, the cost was falling rapidly, mainly driven by the development of the electric vehicle market.

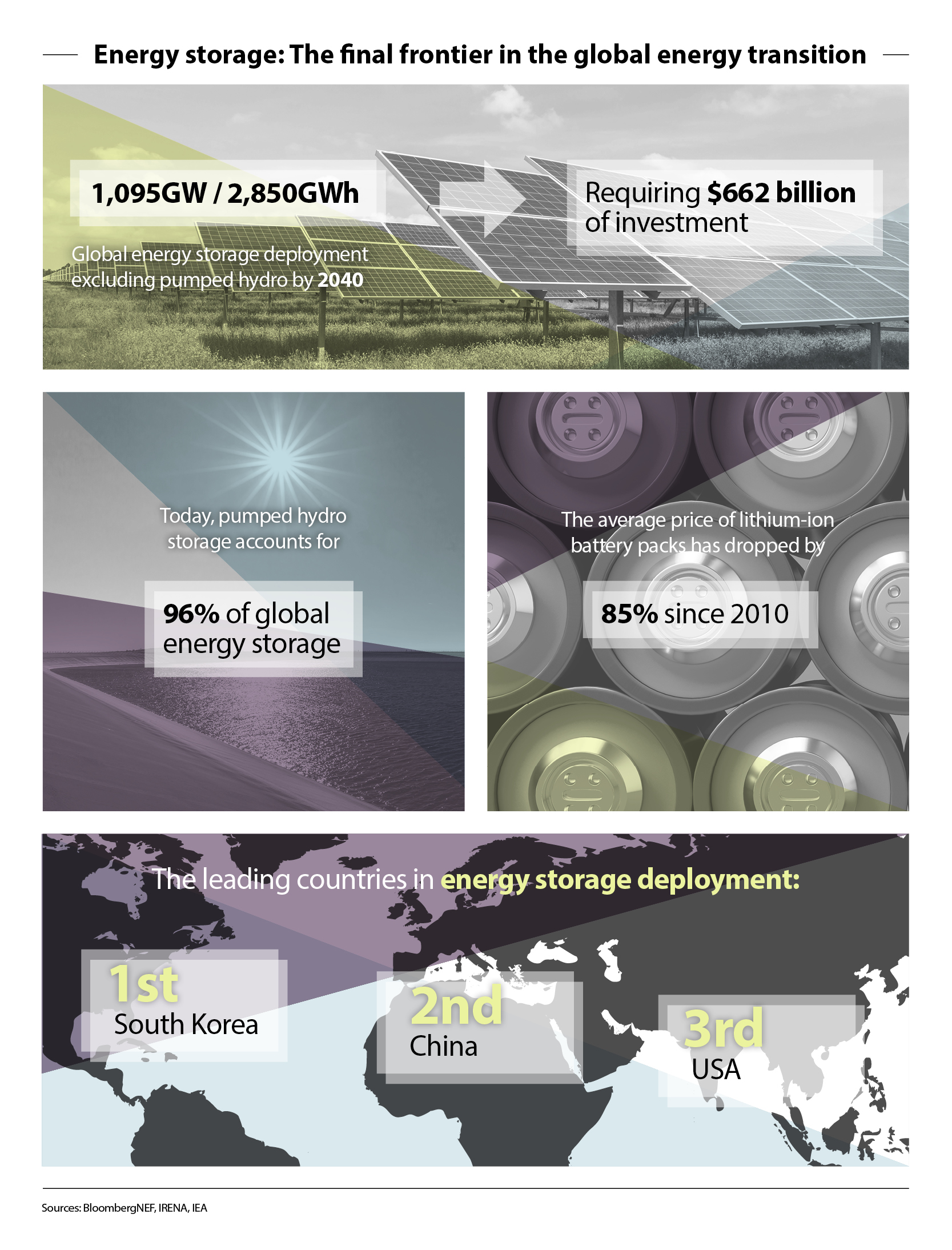

Since then, growth in the stationary storage market has been remarkable. In 2018, deployment grew 147 per cent, and energy research firm Wood Mackenzie predicts that the global market will grow 13-fold by 2024, from 12GWh to 158GWh.

The growth is being driven by a number of factors, including the rapid expansion of wind and solar power and the increasing focus on electric vehicles in transportation. “We’re already seeing that renewable technologies are the cheapest source of electricity in many countries. After 2030, renewables will dominate the electricity system,” says Pilar Gonzales, Innovation Manager at Iberdrola. “Because wind and solar are variable, they need energy storage to integrate them into the system – long duration, daily and minute-to-minute.”

An entirely new sector based on energy storage is emerging, offering services to power users and providers. John Carrington, CEO of Stem, a California-based storage company, says that “the growth of storage is changing the way we produce, manage, and consume energy.”

Stem uses an artificial intelligence software platform to leverage the storage of lithium-ion batteries installed at commercial and industrial sites. “Batteries are dumb. We make them intelligent,” he says. “We can offer a variety of different services at the same time from the same batteries.”

These include frequency regulation where an energy storage system can be charged or discharged to alleviate demands on the grid, peak shaving, which reduces demand enough to remove the need for inefficient peak power plants to be brought online and selling power into the wholesale market.

“Utilities don’t like the exporting nature of solar. Most of the biggest cities are also the oldest, with the oldest grids. We can site batteries strategically near parts of the grid that are most constrained.”

Batteries offer ideal storage for up to four hours, for users ranging from large utilities to industrial facilities and individual households. “If you want to get the most out of the energy you produce at home, then it’s good to have a battery,” Gonzales says, “but it is much more sensible to have a centralised battery. You get more out of it if it is connected to the network, which can move energy from one point to another.”

Solutions are also emerging for personalised energy storage. Tespack, started by former Bolivian Army Special Forces soldier Mario Aguilera, produces wearable technology and portable solar panels that are used by the military, relief agencies and “anyone who lives and works outdoors”. Aguilera’s inspiration for setting up the company was when he experienced loss of power while training with his unit in remote areas of South America. “Everyone should be able to generate their own energy on demand to recharge their own devices,” says Aguilera.

There is also a need for storing energy over longer time frames, for which batteries are ill-suited. The vast majority of long-term storage is pumped hydro and that situation is unlikely to change in the short to medium term.

Despite the geographical constraints to new sites, there is a lot of potential to repower existing hydro facilities. Additionally, researchers are exploring the possibility of creating sub-surface pumped hydro using underground reservoirs such as caverns, abandoned mines and man-made reservoirs.

Other options include compressed air energy storage, whereby compressed air is stored in underground caverns. When the air is decompressed through a turbine the resulting energy powers a generator. This solution has shown some promise but again needs specific geographical conditions. There are only a few projects in operation or under construction, mainly in the US and Germany, and one of the technology’s biggest challenges is the amount of energy lost in compressing and decompressing the air.

The same issue affects hydrogen storage, which is seen as a long-term solution because it can be used in cars, shipping and aviation, as well as to produce power. “There is potential for hydrogen production, but the problem is efficiency and cost,” says Iberdrola’s Gonzales. “The efficiency of using electricity to produce hydrogen and converting it back to electricity is only about 30 per cent and the costs are very high.”

Notwithstanding exponential growth, surging demand and a raft of new technologies, the sector is still, ultimately, nascent. Stem’s John Carrington observes, “Making money out of long-term storage is tough. I do think we will see seasonal storage in the next few years, but it will be a different technology. The cost has to be so low to make it viable and no-one has figured that out yet.”