Richard Thurlow saw the opportunity early. Having worked on boats since he left college, in a variety of roles including fishing and contracting for the Ministry of Defence, he was hired as skipper of a crew transfer vehicle for the first commercial offshore wind farm in the UK, at Scroby Sands off the coast of Great Yarmouth. Soon after, he bought his own boat and created a company, Iceni Marine Services, to transport workers to and from the wind farms that now dot the North Sea.

“We eventually grew the company to six vessels and sold it to Glasgow-based Turner Group. We’re now called Turner Iceni and we have 12 boats,” he says. “The offshore wind industry is just going to snowball. The technology is getting better all the time. When I started the turbines had a capacity of 2MW. Now they’re 8MW and getting bigger all the time.”

“This is an industry that will have gone from absolutely nothing at the turn of the century to 10GW by the end of the decade",” says Jonathan Cole, Global Managing Director of Offshore Wind at renewable energy developer Iberdrola. “We have taken a nascent technology that might contribute to cutting emissions at some stage if we could sort out the technological issues, and turned it into the backbone of a modern, clean, green, smart energy system.”

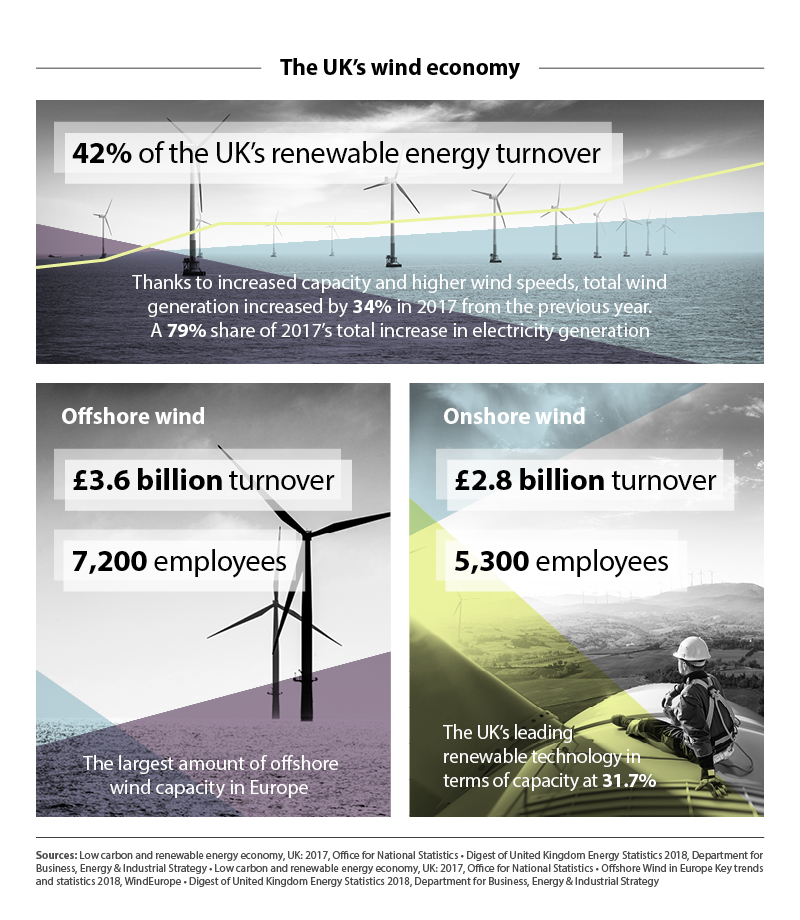

More than £30bn of private sector capital is being invested in the UK offshore wind sector, and the sector now produces enough clean electricity to power about 8m homes, he adds. “Along the way, we’ve also invested in a workforce that is about 10,000 strong, who are working in highly-paid, highly-skilled jobs, many of them in post-industrial towns that really need this investment.”

A government-funded course is helping unemployed people to retrain to become wind turbine engineers in regions such as the East of England. “People tend to think of the region as being mainly about food production and tourism,” says Simon Gray CEO of the East of England Energy Group. “They don’t know about our pedigree in energy. We have had more than 50 years of nuclear power at Sizewell and Bradwell, more than 50 years of gas production. People are now migrating from these sectors – and fishing – into offshore wind.”

The sector will be bolstered by the UK government’s recent decision to commit to a net zero carbon target by 2050, and the more specific goal of delivering 30GW of offshore capacity by 2030 and 75GW by 2050. “I absolutely believe we can deliver that,” Iberdrola’s Cole says. “We have always exceeded expectations so far.”

The East of England is well placed to benefit from the growth in offshore wind because of the North Sea’s strong winds, shallow waters, foundation-friendly seabed and proximity to the electricity markets of London, the South East and the Midlands, East of England Energy’s Gray points out.

Once the turbines are installed, they will be in operation for 25-30 years, during which time they will require considerable maintenance. “That’s the real prize – the operation and maintenance contracts. That’s two generations of workers, employed in skilled jobs.”

By contrast, onshore wind is not fully meeting its potential in the UK at the moment, thanks to the government’s de facto ban on the sector, but with the adoption of the net zero target, it is hard to see how this will stand.

The UK, although it is the leading market in offshore, is not developing in isolation, of course. Other promising markets in Europe include Germany, France, Denmark and the Baltic states. “More or less anyone with a shallow coastline is going big on offshore wind because they need to decarbonise and the costs are coming down so quickly,” Cole says.

As all the shallow water sites are developed, the industry will turn its focus to deep water projects, which will require floating turbines. This is a technology that is still in its infancy, but it will develop even more quickly than fixed turbines, Cole says. “Floating structures will be massive, but once they have been perfected, the same equipment can be used anywhere and the industry will be able to scale up much faster than fixed turbines, with costs falling more rapidly as a result.”